when was invented the computer

when invented the computer

who invented the first computer

what year invented the computer

when was the first computer invented

when invented the first computer

who invented the computer and when

who and when invented the computer

how invented the computer

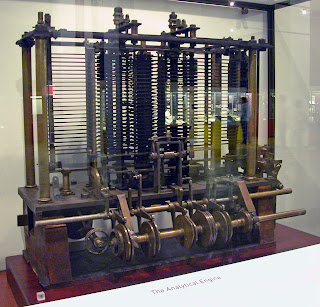

As we probably are aware in 19 century Charles Babbage the well known Mathematics educator had its start. He structured the Analytical Engine (first mechanical computer) successor of the Difference Engine (automatic mechanical calculator) which is known as a fundamental system for the present computer. It is grouped into ages and every age is its improved and changed rendition.

In 1822, British mathematician and designer Charles Babbage (1791-1871) fabricated the steam-fueled automatic mechanical calculator what he called "Difference Engine" or "Differential Engine". It was in excess of a straightforward calculator. Which is fit for registering a few arrangements of numbers and accordingly it gives printed versions. Ada Lovelace helped Charles Babbage in the improvement of different engines. It figures polynomial conditions and print scientific tables automatically.

In 1837, Charles Babbage assembled the first portrayal of a general mechanical computer, which was the successor of the Difference Engine what he called the analytical engine, yet never finishing while Babbage was alive. It was customized to utilizing coordinated memory and punch cards.

In 1991, Henry Babbage, Charles Babbage's most youthful child complete a bit of the machine that perform essential figurings.

We could contend that the first computer was the math device or its relative, the slide rule, designed by William Oughtred in 1622. Be that as it may, the first computer looking like the present current machines was the Analytical Engine, a device imagined and planned by British mathematician Charles Babbage somewhere in the range of 1833 and 1871. Before Babbage tagged along, a "computer" was an individual, somebody who truly lounged around throughout the day, including and subtracting numbers and entering the outcomes into tables. The tables at that point showed up in books, so others could utilize them to finish assignments, for example, propelling big guns shells precisely or computing charges.

It was, truth be told, a mammoth calculating undertaking that motivated Babbage in the first spot [source: Campbell-Kelly]. Napoleon Bonaparte started the undertaking in 1790 when he requested a change from the old magnificent arrangement of estimations to the new decimal standard for measuring. For a long time, scores of human computers made the fundamental transformations and finished the tables. Bonaparte was always unable to distribute the tables, be that as it may, and they sat gathering dust in the Académie des Sciences in Paris.

In 1819, Babbage visited the City of Light and saw the unpublished original copy with page after page of tables. Assuming just, he pondered, there was an approach to deliver such tables quicker, with less labor and fewer slip-ups. He thought of the numerous wonders created by the Industrial Revolution. In the event that innovative and persevering innovators could build up the cotton gin and the steam train, at that point why not the machine to make estimations [source: Campbell-Kelly]?

WHEN INVENTED THE COMPUTER

Be that as it may, as you may have speculated, the story doesn't end there.

A few people may have been debilitated, however not Babbage. Rather than improving his structure to have the Effect Engine simpler to manufacture, he directed his concentration toward a considerably more stupendous thought - the Analytical Engine, another sort of mechanical computer that could make much increasingly complex estimations, including augmentation and division.

The essential pieces of the Analytical Engine look like the segments of any computer sold available today. It included two signs of any cutting edge machine: a focal handling unit, or CPU, and memory. Babbage, obviously, didn't utilize those terms. He considered the CPU the "plant." Memory was known as the "store." He additionally had a device - the "peruser" - to include guidelines, just as an approach to record, on paper, results created by the machine. Babbage considered this yield device a printer, the antecedent of inkjet and laser printers so regular today.

Babbage's new innovation existed as a rule on paper. He kept voluminous notes and portrays about his computers - almost 5,000 pages' worth - and in spite of the fact that he never manufactured a solitary generation model of the Analytical Engine, he had an unmistakable vision about how the machine would look and function. Getting a similar innovation utilized by the Jacquard loom, a weaving machine created in 1804-05 that made it conceivable to make an assortment of fabric designs naturally, the information would be entered on punched cards. Up to 1,000 50-digit numbers could be held in the computer's stockpiling. Punched cards would likewise convey the directions, which the machine could execute out of successive requests. A solitary specialist would direct the entire activity, yet steam would control it, turning wrenches, moving cams and bars, and turning gearwheels.

Shockingly, the innovation of the day couldn't convey on Babbage's goal-oriented structure. It wasn't until 1991 that his specific thoughts were at long last converted into a working computer. That is the point at which the Science Museum in London worked, to Babbage's definite details, his Difference Engine. It stands 11 feet in length and 7 feet tall (multiple meters long and 2 meters tall), contains 8,000 moving parts and gauges 15 tons (13.6 metric tons). A duplicate of the machine was assembled and transported to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., where it stayed in plain view until December 2010. Neither one of the devices would work on a work area, yet they are no uncertainty the first computers and forerunners to the cutting edge PC. Also, those computers impacted the advancement of the World Wide Web.

Analog computers:

During the first 50% of the twentieth century, numerous logical computing needs were met by progressively advanced analog computers, which utilized a direct mechanical or electrical model of the issue as a reason for calculation. Be that as it may, these were not programmable and for the most part, came up short on the adaptability and exactness of modern advanced computers. The first modern analog PC was the tide-anticipating machine, developed by Sir William Thomson in 1872. The differential analyzer, a mechanical analog PC intended to understand differential conditions by incorporation utilizing haggle systems, was conceptualized in 1876 by James Thomson, the sibling of the more well known Lord Kelvin.

The specialty of mechanical analog computing arrived at its peak with the differential analyzer, built by H. L. Hazen and Vannevar Bush at MIT beginning in 1927. This built on the mechanical integrators of James Thomson and the torque intensifiers imagined by H. W. Nieman. Twelve of these gadgets were built before their out of date quality got self-evident. By the 1950s, the accomplishment of computerized electronic computers had spelled the end for most analog computing machines, yet analog computers stayed being used during the 1950s in some particular applications, for example, training (control frameworks) and airship (slide rule).

Who Invented the First Electronic Digital Computer?

At college of Pennsylvania J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly invented ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) in November of 1945, it was structure and development was financed by the US military. It was involved 1800 square feet, 200 kilowatts of electric power, 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors, and 18,000 vacuum tubes were utilized and its weight was very nearly 50 tones. In spite of the fact that ABC computer was the first digital computer however many still consider the ENIAC was the first digital computer since it was the first operational electronic digital computer. It was utilized for climate forecast, nuclear vitality counts, warm start, and other logical employments.

Who invented the first programmable computer and where?

In 1938, German structural specialist, Konrad Zuse fabricated the world's first uninhibitedly programmable double determined mechanical computer what he called Z1. Konrad Zuse has thought about the designer of the advanced computer. It was programmable by means of punched tape or punched tape peruser.

Z1's unique name was "V1" for VersuchsModell 1, after World War 2 it renamed "Z1". It comprised of around 1000 kg weight with meager metal sheets with 20000 sections.

Who invented the first business Computer?

In 1951, the first business computer that handles both numerical and alphabetic and created in the US what he called UNIVAC I (Universal Automatic Computer I). It was structured by J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, who were the innovators of ENIAC. It was a vacuum tube, restricted speed of memory computer that was utilized by the US military and its information and capacity was attractive tape or an attractive drum.

Computing in Ancient Times

In spite of the fact that Babbage is properly viewed as the dad of present-day computing, two ancient gadgets are frequently thought to be the main simple PCs: the south-pointing chariot in China and the Antikythera mechanism in Greece.

The south-pointing chariot was an adjustment of a fifth-century BC heavily clad carriage called the Dongwu Che. The south-pointing highlight was included around the first century BC. It didn't utilize magnets; the course was set toward the beginning of an adventure and depended on a gear framework connected to the wheels to alter its heading.

The Antikythera mechanism was an orrery (used to decide galactic positions). It was found in 1901 on a wreck in the Greek islands. The gadget has been dated to at some point between 205 BC and 60 BC. It contained in excess of 30 cross-section gear wheels, a fixed ring dial, and a hand wrench.

After the breakdown of Ancient Greece, the innovation was lost for over a thousand years. It wasn't until the appearance of mechanical cosmic checks in Europe in the fourteenth century that human advancement saw comparative degrees of innovative multifaceted nature.

The Modern Contenders: John Blankenbaker, Xerox, and IBM

Obviously, the Manchester Electronic Computer was as yet far from the machines we use today. Yet, by the mid-1950s, the pace of advancement was developing exponentially. The pace of improvement is one of the many reasons why you shouldn't trouble future-sealing your computer.

1953: IBM discloses the 701, the world's first logical computer.

1955: MIT dispatches Whirlwind, the first computer with coordinated RAM.

1956: MIT demos the first transistorized computer.

1964: Italian Pier Giorgio Perotto discloses the Programma 101, the first work area machine. 44,000 were sold.

1968: Hewlett Packard began selling the HP 9100A. It was the first mass-promoted personal computer.

Thus to the 1970s. American John Blankenbaker made what many specialists consider to be the first PC—the Kenbak-1. The computer went marked down in 1971; only 50 machines were constructed. They sold for $750, which is about $5,000 today.

Be that as it may, even the Kenbak-1 was a long way from the present machines. It utilized a progression of switches and lights for contributing information.

The first computer that took after a modern machine was the Xerox Alto (1974). It had a showcase, GUI, and mouse. Applications opened in windows and symbols, and menus were ordinary over the working framework. The Xerox Alto never went on a general deal, yet around 500 were utilized in colleges around the globe.

Steve Jobs got a demo of the Alto in 1979; the ideas it utilized shaped the premise of the Apple Lisa and Macintosh frameworks.

At long last, in August 1981, IBM discharged its Personal Computer. The open engineering machine was in a flash mainstream, offering to ascend to a large group of perfect projects and peripherals. Inside a time of its discharge, there were 753 programming bundles accessible, multiple occasions the same number as on the Apple Macintosh a year after its discharge.

ACTUAL REAL INVENTOR OF COMPUTER

MAIN INVENT OF COMPUTER

In the event that somebody up and asked you "who invent the computer," how might you react? Bill Gates? Steve Jobs? Al Gore? Or on the other hand, say you're all the more generally keen, may you adventure Alan Turing? Maybe Konrad Zuse? Turing is the person who, during the 1930s, laid the preparation for computational science, while Zuse, around a similar time, made something many refer to as the "Z1," by and large credited as "the first unreservedly programmable computer."

But then the entirety of the above could refute, contingent upon what a British research group and a huge number of dollars turn up throughout the following decade.

The group's inquiry, as presented by the New York Times: "Did a flighty mathematician named Charles Babbage think about the first programmable computer during the 1830s, a hundred years before the thought was advanced in its cutting edge structure by Alan Turing?"

You know, Charles Babbage? Conceived in 1791, kicked the bucket in 1871? Who endeavored to build something many refer to as a "Difference Engine" during the first 50% of the nineteenth-century, a sort of mechanical adding machine intended to figure different arrangements of numbers? Some contend that he, not Turing or Zuse, is the genuine dad of the advanced computer.

I worked for an organization named after the person in 1994. You know, Babbages, the shopping center based chain that in the end converged with Software Etc. before its parent organization failed, it was gotten by Barnes and Noble's Leonard Riggio, and in the long run, collapsed into the current GameStop chain. I recall our store had a silver plaque on the front side of the money wrap with a carving of Babbages and a short review clarifying what his identity was and why the odd-sounding name fit a store that, at the time, sold for the most part PC-based items.

Babbage never fabricated his Difference Engine—a mechanical adding machine with a great many parts—as a result of cost invades and political contradictions, yet the innovator passed on plans for its fruition, and in 1991, the Science Museum in London really constructed it (the printing segment was done in 2000). As suspected, it really works.

However, the Difference Engine could just do repetition figurings and was unequipped for checking its outcomes to modify the course. Babbage in this manner had greater plans to develop something many refer to as an "Investigative Engine," a beast machine the size of a stay with its own CPU, memory and equipped for being customized with punch cards, that he'd envisioned however never had the fortitude to build, past a preliminary piece, before his demise. The issue: Where the Difference Engine's plans were finished, the Analytical Engine's were a work-in-progress.

Enter the Science Museum of London, which plans to build Babbage's Analytical Engine a century-and-a-half later, and cure the work-in-progress obstacle by putting the plans online one year from now and welcoming the bystander to say something. One of the focal inquiries the ventures intended to answer is whether Babbage would have had the option to really build it by any means.

On the off chance that the appropriate response's definitive "truly, he could have," it could challenge the overall scholastic conviction that Alan Turing, not Babbage, structured the first universally useful computer. And keeping in mind that the inquiry today is absolutely scholarly, the machine's development, expecting it truly is feasible, ought to demonstrate entrancing to watch.

No comments:

Post a Comment

IF YOU HAVE ANY DOUBTS, PLEASE LET ME KNOW